Observed in life and reinvented in paint – an interview with Judith Linhares

by Sandino Scheidegger

You’ve now lived in New York for exactly as long as you lived in California. Forty years. How has Bay Area culture from the ’60s and ’70s influenced your paintings up to now?

I think we are all far more informed by the times we live in and the reactions and signals we receive from the people around us than we care to realize or admit.

Growing up, I was aware of how my California relatives defined themselves. “We are not like those East Coast people,” they would say, meaning the kinds of people who are exclusively concerned with credentials. The story went that in the West, you had the freedom from history and tradition as well as the physical space to be your own person.

Early on, coming of age in Los Angeles in the ’50s, the notion of what it was to be “modern” was in full view. There was very little sentimentality about the past or about keeping things the way they were. I saw a lot of great modern art at the L.A. county museum, the abstract expressionists already being a well-established and well-represented school of painting at the time. People were coming to the West Coast from all parts of the country, to reinvent themselves and fulfill their dreams of becoming something else. Which is quite different from New York, where people would move in search of rigorous thinking and validation.

"My motivation comes from the desire to immerse myself in the process of painting, to feel the power of invention and concoct a coherent and believable form using space and light. "

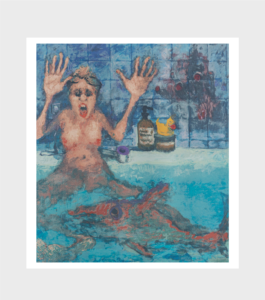

FIRE SIDE

Silkscreen print, 29.1 x 34.5 in. (74 x 87.7 cm)

Produced on 320 g 100 % cotton Canson paper

How is culture viewed differently in New York than in California?

New York is an older city with world-class museums and many connections to Europe. It is easy to meet other artists in New York. They are all prepared to talk and have opinions about what art is and what it needs to be doing. There is an urgency about ideas and the importance of culture in New York.

Artists in California, on the other hand, are less involved with having a conversation with history. California offers solitude and freedom from the march of history, freedom to invent yourself.

Shortly before moving to New York, you were included in the influential “Bad” Painting show at the New Museum, curated by Marcia Tucker. The show’s ironic title was also the name given to a trend in American figurative painting that broke with traditional approaches in favor of a more personal style of figuration. Was there ever any kind of cohesion between the figurative painters of the time (as with the American abstract movement), or was it a more loosely-bound group? How did you relate to your contemporaries and fellow artists in the show?

Marcia Tucker was a visionary curator who set out to explore American art in the ’70s. She was egalitarian in her thinking and wanted to explore a wide range of ideas about what art could be. Marcia thought American museums could be more inclusive and more responsive to ideas germinating in the present.

The “Bad” Painting exhibition very consciously set out to include people from every part of America. Places like Chicago, Los Angeles, Texas, and San Francisco all had unique art scenes, all of which were considered provincial by New York standards. Each of these areas was represented in her show, as well as a wide range of ages and approaches to materials and processes.

I knew many of the artists in the show. I was in conversation with people like Jim Albertson from having lived in the Bay Area. Some artists I met as a result of the show, like Charles Garabedian, who later became a friend.

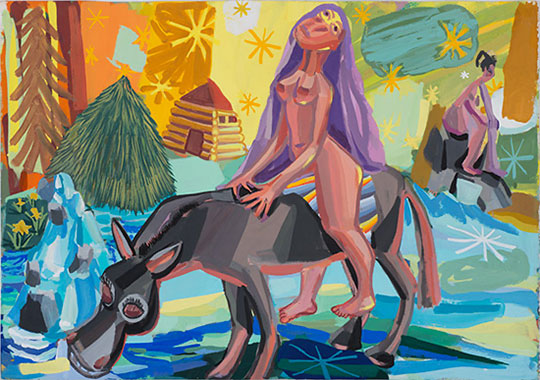

Your work is full of wonder and depicts a world all its own, painted with lush colors and dreamlike landscapes. Is the viewer diving into “Judith’s world,” one that echoes or represents something inside of you? Is it an imagined world carefully painted out of fantasy?

The imagery in my work arrives through the process of painting. I imagine figures or animals in specific environments like the sea, the forest, the desert, the mountains, performing tasks like digging, sweeping, swimming, sleeping, eating, or showing agency and appetite.

I am interested in the curative power of narratives. I am inspired by mythology and fairy tales because they tell of conflicts that are common to everyone. Things like needing to prove yourself before you can move on, needing to be released from a witch or mad king that has cast a bad spell on you, and so on.

In these stories, the protagonist often faces their task alone, with no other allies apart from ambassadors from nature like ants, birds, frogs, or spirits. My paintings represent a heightened narrative moment before a conflict is resolved.

Your paintings often depict strong women, playful animals, and bouquets. Are these protagonists taken straight from your own life? Where does your lifelong fascination for them come from?

The women, animals, and flowers are inventions, but they have parallels in real life to my mother and aunt, who were both independent and athletic women that followed their own paths and could change a tire if the occasion arose. Many of the details in my paintings like patterned blankets and textiles are observed in life and reinvented in paint.

My motivation comes from the desire to immerse myself in the process of painting, to feel the power of invention and concoct a coherent and believable form using space and light.

You are about to release a silkscreen print with Multiplo, produced by the master printermaker Arturo Negrete Cuellar in Mexico City. How do you compare the practice of printmaking to painting, and what motivated you to explore it?

Making art more affordable has been an interest of mine from the beginning. I remember when I was a poor art student in San Francisco, I would go to a local book store where they sold art prints. I bought an Albrecht Dürer print of Adam and Eve, which I kept for years and always remained important to me as an artist.

I am very enthusiastic about participating in Multiplo’s project. It echoes my concern that art should be more available to more people. I have worked with many great printers and I always learn from collaborative situations like these.