A swimming woman with a painting mind – an interview with Mira Schor

by Julia Bachmann

Dear Mira, the election in the United States has happened. How do you feel now and how did you feel before?

On the day trump was inaugurated, January 20, 2017, I participated in J20 Speak-Out at the Whitney Museum. I began my remarks in the format of a series of Tweets. The first was:

Lay in bed 1 morning last summer & thought, if Trump is elected my life will be shortened #premonition

Evidently that summer I knew in my bones that he was going to win the election. My parents were refugees who escaped the Holocaust by sheer chance and luck—they were in Paris when the Second World War began, escaped towards the South to Marseilles, were able to get an immigration visa to the US, arriving in New York City four days before Pearl Harbor. Their miraculous survival and the loss of their entire families in Poland haunted me always and has made me very alert to the growth of fascism and authoritarianism in the US. I have a very strong built-in fascism Geiger Counter and although now trump has been defeated the meter is still set on high even though the absolute worst has been averted.

In general, all my work has had a political dimension even when it doesn’t look like what people think of as political art. From when I was a young woman painting autobiographical self-portraiture in nature I’ve followed an agenda I set for myself by the time I received my MFA: To bring my experience of living inside a female body—with a mind—into high art in as intact a form as possible.

More recently I added a coda: The work has to be an expression of who I am right this minute.

In that spirit, I created about 300 works on paper where the events of the day and how I felt as a body “right this minute” were articulated through a symbolic language, with trump represented by a red tie, often associated with a small withered limp penis and grotesquely sagging testicles. From these I produced a number of small intense paintings, often with a viscous oily black ground which to me was a representation of what it means to live under fascism, the idea that even the air resists and oppresses you. In some paintings, I just represented snippets of things trump said—representation of language has been a recurring major aspect of my work.

With a few notable exceptions, such as Guernica and the work of the Mexican Muralists, works done with a direct political motivation are often not seen widely at the time they are done. Among my models are Philip Guston’s Poor Richard series of drawings about Richard Nixon, which in fact were shown by Hauser & With in NYC in their entirety for the first time before the 2016 election. Another model for me was Nancy Spero’s extraordinary series of works on paper, Codex Artaud. As this episode in American history comes to an end, I wonder at the fate of the work I’ve done. I think it will be a while before people are interested in looking back.

The other thing I did during this time was to occasionally annotate or correct The New York Times. I’d post these on Instagram and Facebook and they gained a small audience who felt good knowing they were not alone. I don’t think of these as art, in the same way, I do my other work, but there’s been a development of greater interest in them—as the election neared, people who ordinarily try not to think too much about politics became more engaged.

Last year my work moved in a different, more philosophical direction: the trump drawings and paintings, and the Times interventions were hot, these new works are cooler or quieter, as they focus on history and time and the being of an artist. I’ve had a studio residency in Brooklyn the past year where I’ve been able to work very large for the first time in my life but March 18 when New York City was about to go into lockdown I had to go out there, grab what supplies I could, and leave two huge pieces on the wall. It was nearly seven months before I could go back. That was kind of traumatic.

Ironically, as the world has changed in the past four years Americans began to talk about moving to other countries, which in fact my family’s experience has taught me is very hard unless you are rich, I found myself occasionally wondering whether perhaps I could move to Berlin! But then I wondered what I would do with the artworks my parents created in America. I would say the past four years I was gripped and driven by pre-traumatized fear.

In the intervening four years I have been active politically, participating in a number of demonstrations and marches and also being involved with a wonderful project called Learn As Protest, started by art dealer Jeff Bergman who hosted weekly lunchtime readings of literature, newspaper editorials, poetry, historical texts with a kind of self-selected group of artists, writers, poets, and some of their students, at trump tower (these can be viewed currently on Facebook)—by the way I never capitalize his name and I have only ever referred to him as “the current occupier of the White House,” never as President. I became a Twitter addict. And I produced a lot of work that in various ways represented my political rage.

"So the paintings are still personal in enacting the being of a thinking woman, poetic, political, philosophical. "

You attended the California Institute of Arts’ ‘feminist program,’ for which you moved from New York to California. That was in the 1970s, when liberation movements came up. How was the program received within the school and why did you leave the program after a year?

I always made art and by my late teens some of the characteristics of my work—small scale, figuration, narrative, autobiography, satire—were already evident. I was an art history major in college at NYU, I studied with H.W. Janson himself, but I realized that I didn’t want to pursue art history as a profession. I identified with the other side of the slide projector! I decided to go to graduate school in art. I was discouraged by a close family friend, the artist Jack Tworkov, from applying to the major art school in the United States, such as Yale where he had recently been Chairman of the Department of Art—I think he was both concerned I wouldn’t get in but that if I did I would be destroyed by the criticism. Jack didn’t quite say this but “Go West, young man“ is a well-known American motto from the 19th century period of western expansion and Manifest Destiny. Through my sister’s friend, the graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, I heard about an experimental art school that was just opening in Los Angeles, The California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts. It sounded really interesting. I applied. At that time I was working for Red Grooms who wrote a great illustrated letter of recommendation for me to Allan Kaprow!

Sheila, who was just starting a feminist design program at CalArts, told me that there was going to be a Feminist Art Program there to be run by Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago. I met with Miriam in New York and Sheila sent me some feminist publications. I was very interested. It was the beginning of the Women’s Lib movement and my older sister, the feminist literary scholar Naomi Schor, was very involved with feminism. In general it was a very politically active time, with the women’s liberation movement and feminism and then gay liberation emerging from the Civil Rights Movement of the 60s and the anti-war movement. The 70s is now thought of as a time of decline in the US but I think of it as the last great decade of American history!

When I got to CalArts in the fall of 1971, I had to decide whether I would be in the Feminist program or not. CalArts in a very unique way was a kind of last educational expression of the spirit of 1968. As a graduate student I had very few required classes. The Feminist Program was an all-encompassing program, more than a major. It was an educational experiment contained within an educational experiment. It was exclusionary—no men—and it encompassed studio practice and art history classes, since we were working in the immediate wake of Linda Nochlin’s 1970 landmark article, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Consciousness raising was an important component with the focus on developing subject matter for art from women’s experience (this was in the era where aside from Pop Art and a few regional movements like The Hairy Who, the dominant art was abstract and at that time minimalist and such personal content was abhorrent). So it was an intensive and emotionally intense commitment.

We worked on campus and then we worked on Womanhouse, a trail blazing installation art project on site in an old villa in Hollywood which was open to the public for the month of February 1972 and received national attention. After that we turned to more conventional studio classes on campus. Towards the end of my first year in graduate school I left the program. I had some differences with the faculty and also for my second year of graduate school I really wanted and needed to have a more general experience of the school.

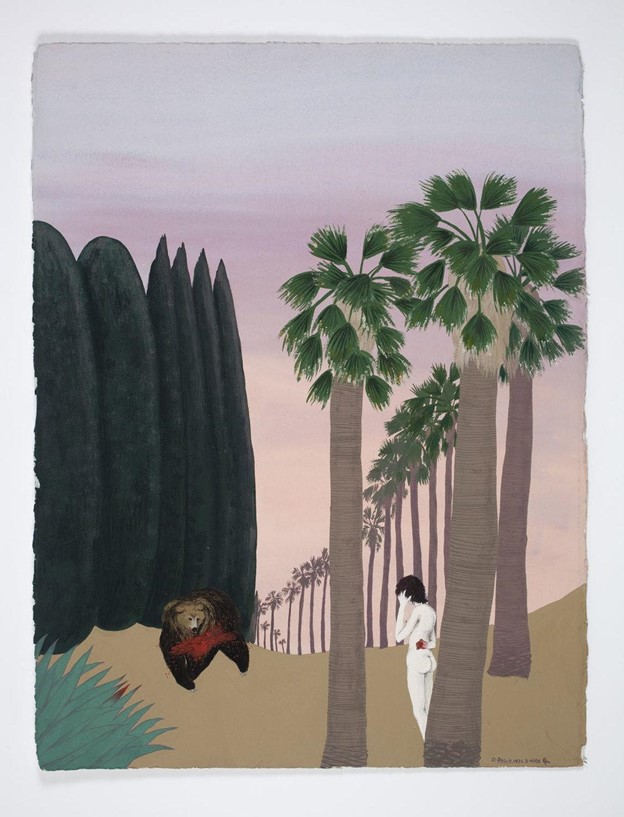

It is just at that moment that I began the group of 9 works + 1 that I call the Story Paintings, of which Bear Triptych was part. What was great about CalArts for me was that really for the first time in my life I felt accepted as myself, as a person and as an artist. There were several important directions represented in the school, Formalism, Feminism, Fluxus, the beginning of the postmodernism—many students of John Baldessari became part of the “Pictures Generation ” by the end of the decade. So my narrative paintings were respected and supported. The second year I worked with a wonderful sculptor, Stephan Von Huene, and I took a class called “The Write of Arting,” taught by Fluxus poet Emmett Williams. All these influences can be seen in my later work as a painter and also as a writer about art. And I got to teach a class of my own design called “Picturemaking,” which drew on all of my visual interests, many of them not part of the modernist canon, whether Kabuki costumes or Early Renaissance painting, and which turned out to be very influential.

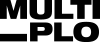

BEAR TRIPTYCH PART I

Silkscreen print, 27 3/8 x 33 in (69.5 x 83.8 cm)

Produced on Fabriano 300gr 100% Cotton Paper

You said about the Bear Triptych—which is part of the ‘Story Paintings’—that it’s highly autobiographical. In it you see a dark-haired, nude woman, situated in the Californian nature, engaging with a bear. There’s blood, wilderness, sensuality and quietness. What is the story behind the bear triptych? How did it feel, having this story exhibited in your graduate show at the university?

My work at that time was in a sense a form of ventriloquism: I could depict in my paintings what I found difficult to express in my life. And I did understand that what I was doing as a woman and as an artist at that time—going against the dominant style and philosophy of art, depicting my dreams and my own sexual and erotic experience in small gouache on paper paintings—had a political dimension. The scenario of Bear Triptych is that of La Belle et La Bête, in a way. The bear is a symbolic representation of a specific person, a short stocky man with black hair and a bushy beard who was in real life my means of finally being rescued from the burden of virginity! The works were about the wildness of sex itself and eroticism was also expressed through the landscape. I often use forms from nature in an animistic way. The big sky, the slightly scary aridity of the High Desert where the school was located, North of Los Angeles, contrasted to the extravagant forms of the in LA’s lush gardens, the palm trees, the Cypress trees, the thorny Agave plants—painting this landscape was another expression of sexuality.

Meanwhile, because CalArts was a small place a lot of people could see the relationship develop in real-time and they enjoyed the Story Paintings the way people look forward to another episode of a TV series. That acceptance on my own terms paradoxically gave me the freedom to move away from that type of work, and once the Story Paintings were done, I moved towards a completely different type of use of space and subject—shifting from narrative landscape and figuration to language itself as subject. Over my career I have in essence shifted back and forth between these approaches, sort of decade by decade.

“Appropriated Sexuality” is the title of your essay on David Salle’s representation of women, which is explicitly misogynous, as you argue convincingly. You see his work as a response to the radical avant-garde feminism that he was exposed to while a student at CalArts. Nobody wanted to publish your essay on David Salle, so in the end it led to the printed magazine M/E/A/N/I/N/G, which you published together with Susan Bee. Did your painting move you to write about art, or did the writing on arts and the publishing of art essays affect your way of painting?

“Appropriated Sexuality” definitely marks a turning point in my work and career. I had a particular insight into the political meaning of Salle’s depiction of women that no one else would have, knowing the rather different work he did as a student of John Baldessari, and knowing that in an ordinary art school, without the presence of feminism as a center of interest and even power in the school—and the thing about CalArts was that because it was a small school with a lot of the work and life taking place on a small campus you didn’t have to study with someone to have a sense of their work—he might have been the school “star.” So I understood his work as a reaction formation against feminism, and I saw the critical acclaim as part of what was described as the Backlash against feminism that began at the turn of the decade.

Writing the essay led to starting my own art magazine, M/E/A/N/I/N/G with another painter, Susan Bee, because I couldn’t get “Appropriated Sexuality” published elsewhere—the last straw was when a small Chicago-based art journal was going to publish it, then showed it to a local author, and published her piece instead, which did exactly what I critiqued the art world establishment of doing, that is, raising the issue of pornography, then laying it aside, and never raising the issue of misogyny which seemed to me to be expressed in the work, in its imagery and artistic approach.

Writing that essay and starting M/E/A/N/I/N/G in 1986, when postmodern theory and “post-feminism” took central stage, led to a big shift in focus in my painting. In the 1970s I had worked in a way that I later came to think of as a dream time. Writing, the research and reading I had to do in order to write at that time, and asserting a critical position in the art world gradually changed my art work away from that dream place to a more sharply focused, more intellectual approach. When Salle was asked what his paintings of women in pornographic positions was about, his terse answer was “irony,” so the first book I read in this new phase was a small book about “irony,” which was a watchword of the time, along with theoretical language coming from authors like Foucault, Lacan, and Derrida. It was a sink or swim situation, you had to learn a new language, or fall out of an important discourse. In general I’ve always been attracted to what seems at first antithetical to me. Paradoxically that’s also the moment when I began to work for the first time in the “master medium,” oil on canvas.

The Swiss Author Julia Kohli writes in her article “Anger of Women“ that women are raised to not be or look angry, since it would affect their attractiveness. She quotes Alena Schröder writing: “anger is a male privilege“ and points out that anger's output can be productivity. (Kohli, J. (2020). Die Wut der Frauen. Das Magazin N°03, S. 7-11)

That’s interesting. Apparently I never learned that lesson! I’ve always had very strong opinions and found it hard to flatter people if I didn’t actually mean what I was saying. The other side of that unfortunate characteristic is that people know that my praise is heartfelt.

After I published “Appropriated Sexuality,” I didn’t fully realize the enemies I had made. I always say that I am extremely risk averse, so I certainly didn’t get up in the morning and think “today I’m going to attack a powerful person in the art world” or think to myself, “attacking important art historians and critics is dangerous but I’ll do it anyway.” I simply felt I had something to say that no one else was saying and I knew I had the capability and the will to take it on. So I did. Several years and many writings later had passed when I mentioned to a noted art historian that I was publishing a second book (A Decade of Negative Thinking) and he asked, “Oh, who are you attacking now?” Then there it was. So be it.

I think women are allowed anger, but only as it pertains to romantic scenarios. Women are supposed to be beautiful, mysterious, they can have a notorious sex life, they can be a “bitch.” That’s different than anger converted into action, in art or activism. But that’s how anger can be very energizing. I got through the trump years by the precise mechanism of instantly converting my outrage—and believe me there were countless days where I thought I would literally “blow my top”—into artworks, literally jumping out of bed after reading the latest Tweet and turning it into a drawing or painting. There is actually a link in many of the works I did the past four years to some of the underlying structure of my Story Paintings including Bear Triptych: a woman faced with a dangerous creature, in a battle for autonomy, turning anger into action and art.

Recently around Halloween I was channel surfing and caught a tiny moment of The Devil’s Doll, a 1935 horror movie, just in time to hear the villain (the actor Lionel Barrymore, disguised as an old woman!) say this most remarkably extreme but eloquent thing, “Without my hatred I could never have lived to exhume myself.”

In the CalArts Feminist Program, one day we were taught to introduce ourselves to people in a professional manner, to say, “I’m Mira Schor and I’m a painter, or, I’m an artist.” Something like that. At the time it seemed silly to me but has stayed with me as an important core lesson. And once a woman takes that step, to identify as an active being operating outside her assigned role within patriarchy, it’s already likely she will be marked as angry. I’m in good company: the day that art historian asked me what I was attacking now, we were attending a public interview with Carolee Schneemann, who certainly was driven by both a great passion for life, and a considerable amount of anger at everything that had ever been placed as an obstacle in her path just because she was a woman. A number of the great artists I most admire work from a sense of anger at injustice—Ida Applebroog, Nancy Spero, Louise Bourgeois, to name a few. But there’s also a lot of humor in my work, there are many dreamlike poetic moments, and there is a relationship to the expressive uses of materials and the sheer sensual pleasure of line and surface.

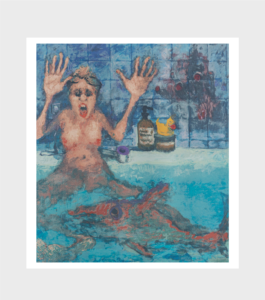

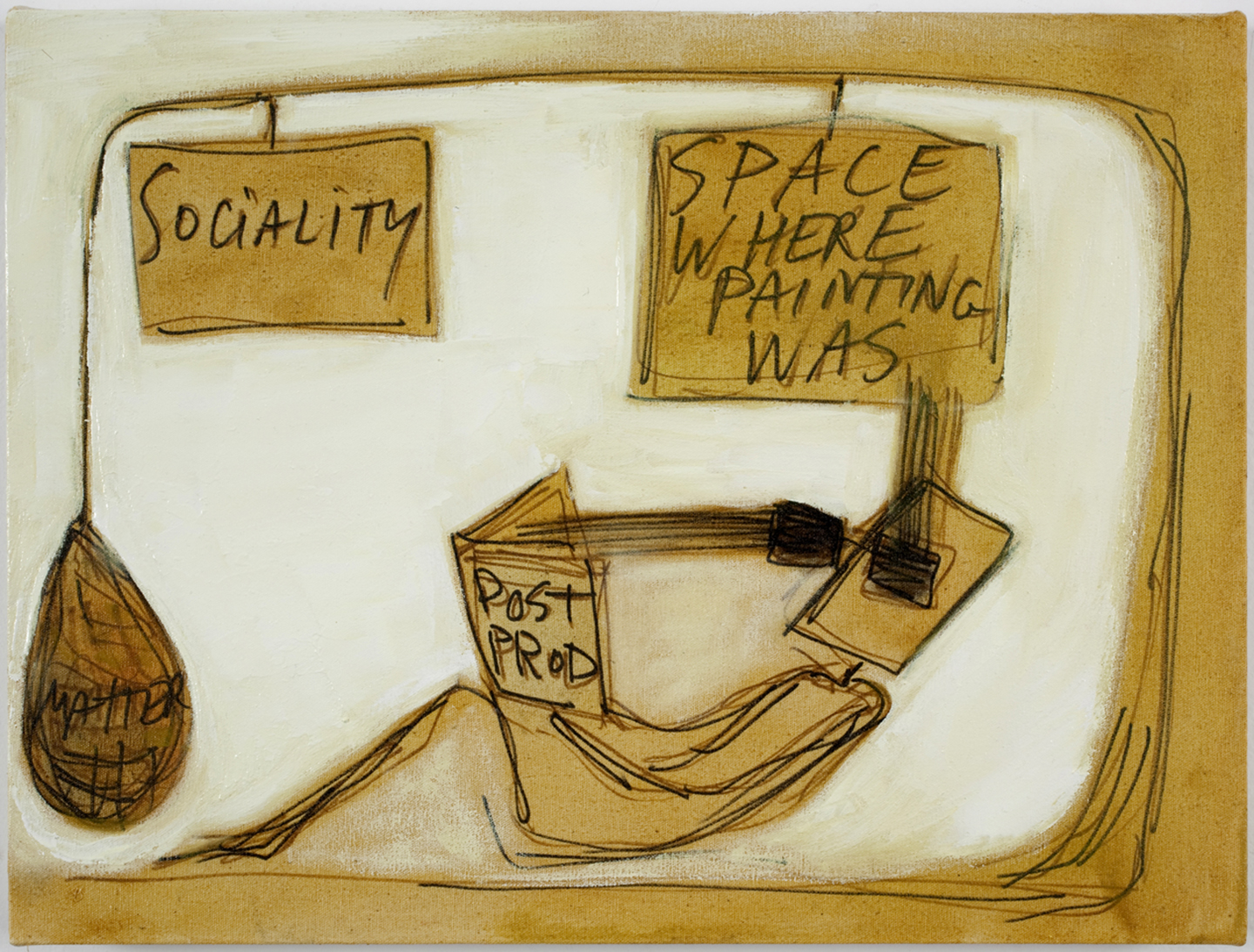

Your paintings in your 2020 solo exhibition at Fabian Lang Gallery in Zurich, “Here/Then, There/Now,” shows painting that were created between 2008 and 2020. Apart from your handwriting, there are paintings of an avatar that is reading, working or sitting. You returned to a walking figure, a thing “with a mind,” but it’s not specifically a female body.

Yes, I never thought I would depict a full human body again after the Story Paintings. There have been representations of an abstracted figure which stood in for the body but whose form was taken from forms in nature, and the human body has appeared, but as selected symbolic parts—ear, penis, breast. The avatar works developed out of the work I began after my mother died. She was an artist, we shared that work and that life. After she died, even my being an artist felt up for grabs. I sat down at her work table to draw, because I didn’t want the table to be lonely. I began with a blob of dense black ink. It turned into a thought balloon, which turned into a head, which then wore eyeglasses and one day developed legs and arms and started to walk off the page and there I was, working figuratively in terms of a figure occupying a space. I added whatever felt necessary in any given painting, including language. The language often came from books I was reading that had a philosophical cast. Here/Then, There/Now was suggested by a book whose title asked the question, What Is Contemporary Art? I felt that the question really should be “Where Is Contemporary Art?,” because of the impact of a much more global art world than the one I grew up in. There (the global art world) is Now but my roots are Here, in the New York art world which is associated to Then, the post-War modernist moment. But you can only work from where you are and do the best you can to be alert.

The figure in the avatar paintings wears a dress but not much else denotes femininity or womanhood though as it’s an avatar of self, it’s female. When you pass a certain age as a woman, actually amazingly early—if you’re 35 and you walk in the street next to a 16 year old girl you experience invisibility!—the world loses interest in your body, and in a way so do you, which can be liberating: you can become a person who sees without being seen and that is a form of power.

The next series of works, the Power Figures I showed at Lyles & King Gallery in New York in 2016, returned a human face to my figuration, albeit often that of a skeleton, and there’s breasts and blood. Though they were on tracing paper which also made them delicate and vulnerable, the Power Figures were very hot and confrontational.

The weirdest thing for me is that in the most recent work I can’t seem to settle on one stable way of representing the body or the self. Sometimes the figure bears a relation to the way figures appear on ancient Greek vases, sometimes like Picasso! Many of the works I did during the pandemic focus on the spaces we have been occupying, our houses, apartments, rooms, whose only occupants are a book, a clock, sometimes a flower growing through the floor.

I’m still working from the agenda I set myself of depicting what it is like to live inside a female body—with a mind. What that looks like may seem very different than the early work, though often it is basically the same premise—a figure in a space or a landscape, and “with a mind,” so the paintings are still personal in enacting the being of a thinking woman, poetic, political, philosophical.

Another artist once said to me, with some surprise, “Your work is about something.” I thought that was funny, I mean isn’t all work about something, but I had a sense of what he meant.

There’s a lot of pressure in the art world to have a signature style and stick with it so your work is a recognizable commodity. In my case, over many years, there are themes, there is a hand, a touch, that is characteristic throughout. Ultimately I see all the work I’ve done as one work, essentially, each painting or drawing being a single frame from a continuously unspooling reel of movie film, which occasionally loops back upon itself, recovering some key element of past work, the way one’s life moves forward toward an unknown but carries everything that happened before.